For books that really hit, I’ve decided to process them a little further in my summary, so others can see what’s inside without doing the work. My goal for these is simple – to get people to buy the book. In that spirit, let’s get started. Promise, I’ll keep it short. Indeed, if you want the TLDR; version – get this book if you want to build your faith; if you’re not a believer, get it to find the heart of a real Christian.

I was turned onto Thomas Cahill when I read his book How the Irish Saved Civilization, which I thought would be a funny, tongue-in-cheek read, but turned out to be real reporting on the history of St. Patrick and how the Irish basically preserved Western Civilization by hiding books for a few hundred years after Rome fell.

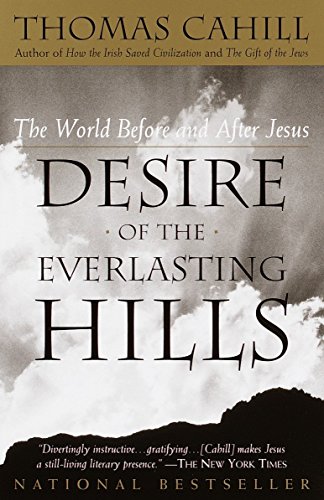

In Desire of the Everlasting Hills, Cahill takes us on the journey of Jesus and beyond. What was the impact of Jesus? What was the world like before him and after him?

I expected history, but what I got was more. It was affirming of the reality of Christ and yet, critical of its followers and how so often throughout time our institutions fail to live up to the simple message of love and acceptance that Christ has put forth. What follows below is just me reacting to the dozens of notes I wrote in the book. It’s a messy note-taking effort, and I don’t try to make it all go together. If you want that, buy the book. 🙂

The Beginning

He starts with Alexander the Great, who, by spreading the Greek language and culture, set the stage. Then it was the Jews’ turn with their victory over the Greeks. One gets a real feeling about how incredibly ancient Judaism is when reading this work. They were everywhere. Jews lived uncomfortably with the Romans, and then in typical Cahill style, he casually introduces the main character.

The year was 31 B.C…. Augustus would prove a proper emperor…[but] those who knew him hated and feared him. He was approaching his fourth decade on the imperial throne when a male baby of uncertain paternity was born to a rural Galilean girl in the emperor’s province of Syria, in the bothersome subdivision the Romans called Judea.

p. 56

Jesus

Jesus keeps two audiences in view – the poor and miserable and those who have a religious obligation to stand with them.

Jesus was a man of the people, and much of the human experience is found in the senses and the small attentions of one human being for another.

Mary

This book is funny in its bluntness. When Mary is told she’s to have Jesus, she says, “This doesn’t make any sense, I haven’t had sex yet.” After the angel’s response, she continues, “Here I am, the Lord’s servant. Let’s get on with it.” He points out that Mary is more of a sensible, down-to-earth peasant girl. Showing the humanity of the Bible characters like this is what sets Cahill apart.

Paul

I like that Cahill incorporates the multiple authors theory of biblical exegesis. I mean, it’s been clear to me that there are many authors, and that’s okay. The revelation comes progressively, even now.

Mary and Joseph are not relegated to a romanticized stable because there was no room for them at the inn. Cahill maintains that this is old and inaccurate information. They were likely relegated to an unused room in a house because of the embarrassment of the pregnancy and the taxman’s arrival (pg 99).

Paul was critical to the spread of Christianity, giving it its intellectual edge, and his theology is as startling as his conversion experience. He was brutally beaten for his beliefs, and yet, stuck with them. As a 22nd century reader in the US, I feel convicted. The comfort I have in my life is so unlike what these men and women suffered. Life always includes suffering; I don’t need to go looking for it, but when it does come, I strive to be as strong as them.

For Cahill, Christians having careers isn’t inherently bad. Paul was a tentmaker. This helped with the income and was portable.

Christian Transhumanism & Equality

Did not Jesus, by his resurrection, by this startling proof of life beyond death, set this process of decay going in the opposite direction? Did he not, in effect, by his resurrection (and the promise of ours) reinstitute the Creation? Is he not, therefore, the New Adam, and are we not the New Creation?

p. 124

Cahill calls 1 Corinthians 13 (“Paul’s ‘Hymn to Love'”) a “Himalayan peak of world literature.”

Note that this book is 20 years old, but Cahill seems prescient in saying that Christianity is more about acceptance and feminism than anything before it.

But equality, not complementarity, is Paul’s subject….Most of us should be cheered that here, plunk in the middle of this old-hat stuff about what to wear, we have the only clarion affirmation of sexual equality in the whole of the Bible – and the first one ever to be made in any of the many literatures of our planet…. In this ancient world of masters and slaves, conquerors and conquered…Paul writes the unthinkable to his Galatians, who may just have been goofy enough to receive it: “There is no longer Jew or Greek, slave or free, male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”…The primitive Church was the world’s first egalitarian society.

p. 141, 147, 148

The Gospels

Cahill covers the gospels from here and talks about their similarities and differences. I understand now that the Synoptic Gospels are the three that can be read in parallel. Per Wikipedia: “The gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke are referred to as the synoptic [sic] Gospels because they include many of the same stories, often in a similar sequence and in similar or sometimes identical wording. They stand in contrast to John, whose content is largely distinct. “

Turns out that John is very different, sometimes in problematic ways. He has the oldest and the newest stuff, but his Jesus is very unearthly and a bit exclusive, specifically against the Jews. By the time the first letter of John was written, the Jewish Christian Schism that has left its traces in John’s Gospel was already fading into history, and the Johannines had found a new foe – The Gnostics, who preferred to believe that Jesus had never been human anyway, just a spirit who appeared to be a human. John had an important role in defining Christianity later in the first century, which involved judging those who were “in” vs. “out”.

In the midst of all this judgment, we find the story of the adulterous woman, where Jesus was drawing pictures in the dirt (I’ve always wanted to know what he was drawing). Apparently, that story was pulled out of Luke. Early church leaders didn’t want adultery to be forgivable and censored the passage, the first-ever recorded ecclesiastical censorship.

This is the same Jesus who tells us that hell is filled with those who turned their backs on the poor and needy – the very people they were meant to help – but that, no matter what the Church may have taught in the many periods of its long, eventful history, no matter what a given society may deem “sexual transgression,” hell is not filled with those who, for whatever reason, awoke in the wrong bed. Nor does he condemn us.

p. 281

Historical Jesus

Cahill is big on the incredibleness of the Bible, specifically the New Testament.

This phenomenon of consistency beneath the differences makes Jesus a unique figure in world literature: never have so many writers managed to convey the same impression of the same human being over and over again. More than this, Jesus – what he says, what he does – is almost always comprehensible to the reader, who needs no introduction, no scholarly background, to penetrate the meaning of Jesus’ words and actions…. There is no other body of literature approaching its two thousandth birthday of which the same may be said…. To appreciate how singular the gospels are, one should also attempt to comprehend a work like Virgil’s Aeneid, written within a hundred years of the gospels but today requiring months of study of its cultural setting if one is to reach an elementary understanding of its meaning.

p. 284

The Crucifixion

It never occurred to me that Christians of old were severely traumatized by the crucifixion, but Cahill points out that it took nearly five centuries before we saw any art of it. The first evidence is carved in the wood door of the basilica of Santa Sabina on Aventine Hill.

The Shroud of Turin

A big surprise for me is the detail he gives the possibility that the Shroud may be authentic and provides strong arguments for such.

There is no convincing evidence that that image was painted on the cloth. Rather,…the image appears to have been created by intense heat, but heat which did not scorch, a process no one can explain…. If we assume that the Shroud is a clever medieval forgery, we must assume that it was made by an artist whose grasp of the negative-positive properties of photography was five centuries in advance of his time and whose understanding of anatomy was far in advance of that of all his medieval contemporaries. Such a theory, however, falls apart after a careful look at Pia’s negative. Every artist, especially one as facile as the Shroud artist would have to have been, is identifiable by his style, which is as characteristic of him as his signature or thumbprint. The negative image has no style whatever; there is no hand in it. It seems obviously a photograph, that is, an image made by light.

A medieval forger would also need to have been the only human being between the time of the emperor Constantine and our own to have been completely conversant with the details of Roman crucifixion.

p. 289, 291-292

The Finish

The book finishes with flair, dedicating its last pages to how the world has evolved through this epoch.

Through the history of the West since the time of Jesus, there has remained just enough of the substance of the original Gospel, a residuum, for it to be passed, as it were, from hand to hand and used, like stock, to strengthen, flavor, and invigorate new movements that have succeeded again and again – if only for a time – in producing alteri Christi, men and women in danger of crucifixion. It has also produced, repeatedly and in the oddest circumstances, the loving-kindness of the first Christians….

But it is also true that the West could never have realized some of its most cherished values without the process of secularization…. That these values flow from the subterranean river of authentic Christian tradition points up, once more, the paradoxical validity of the distinctions Jesus made between the religious establishment and true religious spirit.

p. 304-305

He claims that we must consider that Christianity’s “initial thrust” has hurled “acts and ideas” not only “across the sanctuaries” but around the world. To me, I interpret this as the Holy Spirit. Cahill doesn’t say it, but this movement, this thrust into the world, is now carried by the spirit, and with that, even those who claim to not follow God are listening to this Spirit. The Creation has been remade.

Cahill ends the book by pointing out the wonderful work of the Community of Sant’Egidio in Italy, founded in 1968 and dedicated to the poor, and scolds Christians for “rejecting Jesus more than any Jew.” He calls for everyone to reassess Jesus, and hopes “that the process of Jewish-Christian reconciliation will soon have progressed far enough that Jews may reexamine their automatic (completely understandable) fear of all things Christian.” He ends with a poem, and I think it perfectly summarizes the work and how it affected me.

He is the Way. Follow Him through the Land of Unlikeness; You will see rare beasts, and have unique adventures. He is the Truth. Seek Him in the Kingdom of Anxiety; You will come to a great city that has expected your return for years. He is the Life. Love Him in the World of the Flesh; And at your marriage all its occasions shall dance for joy. W.H. Auden